I’ve been thinking about 1982… down Memory Lane, along a tortuous, circuitous, cul-de-sac, but such is the way my mind seems to work.

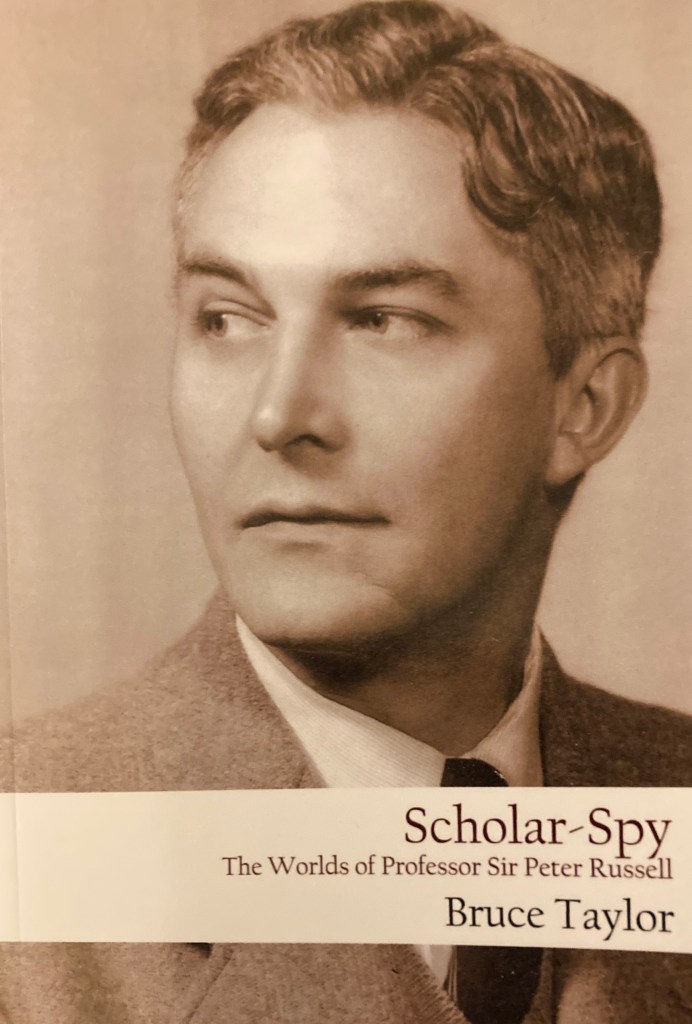

Bruce Taylor has written a biography of my former Spanish professor, Sir Peter Russell, who died in 2006. I’ve just reviewed it for the The Queen’s College website. Sir Peter, his pupil (and my tutor) John Rutherford, and I were all graduates of Queen’s. He lived a full and varied life – “scholar-spy” as Bruce calls him – and I was delighted to be able to contribute a couple of anecdotes to the book.

I mentioned one such anecdote in an earlier blog post. It concerns a comment Russell made during a seminar I attended in 1982 to the effect that, “as someone who knew Lorca, if only slightly, I can assure you that there was no great difficulty in being an homosexual in Spain at that time”. It’s generally known, even in England, that Federico García Lorca, poet and dramatist, was murdered in Granada by fascists at the beginning of the Civil War.

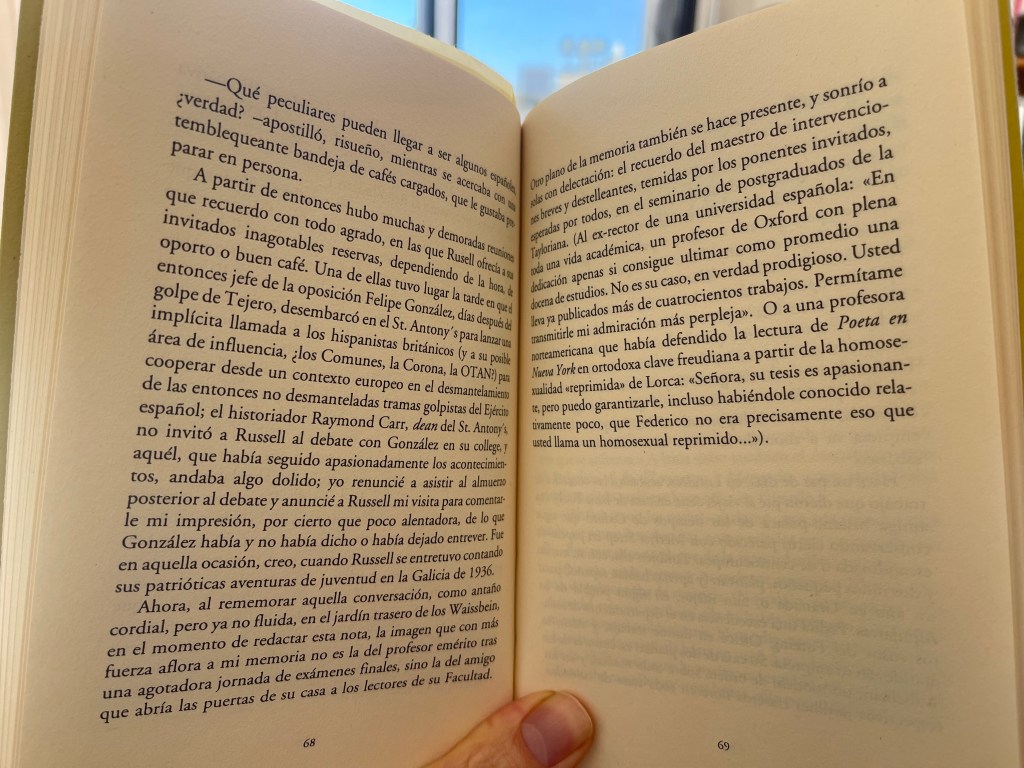

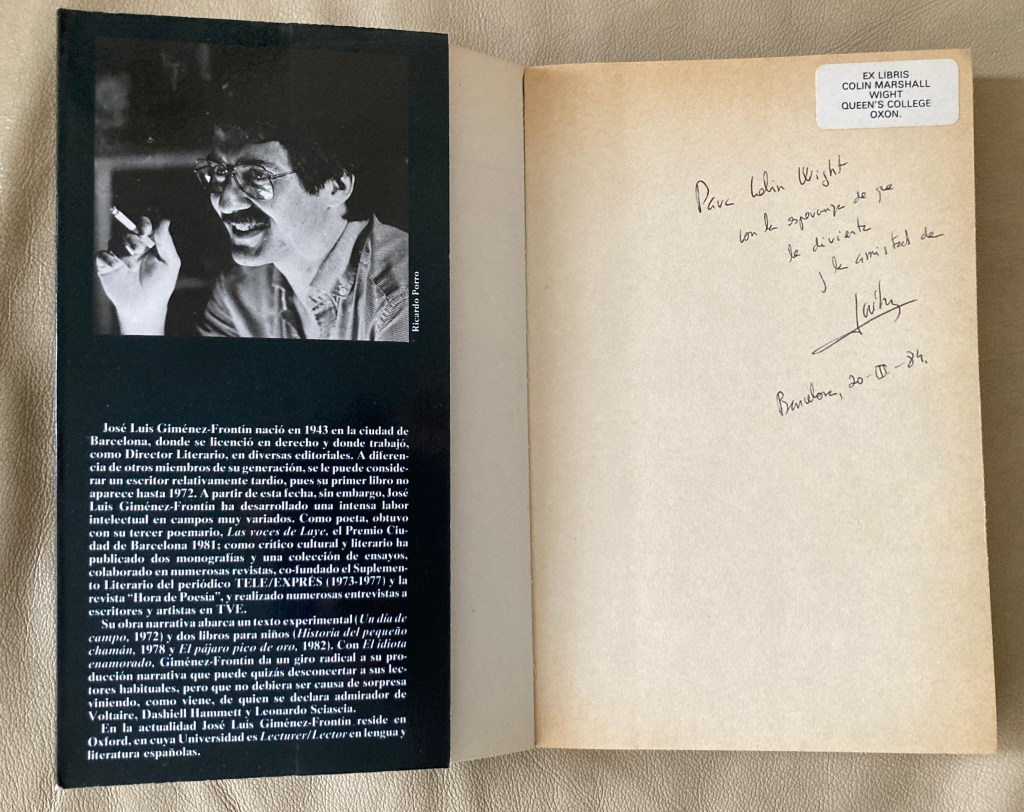

Bruce Taylor told me that the same “Lorca incident” had been recorded by José Luis Giménez-Frontín in Woodstock Road en julio. Notas y diario (1996).

Why had I not read it before?

I got to know José Luis well during his three Oxford years and I remember him also being at that seminar. I managed to access his book online via the Internet Archive.

His recollection of Professor Russell’s intervention is rather different from mine and almost certainly more accurate. I imagine he jotted it down shortly afterwards, whilst I (not keeping a diary at that time) was casting my mind back more than 40 years. The gist is, however, substantially the same. He considered it significant enough to warrant recording; it was not every day that you met someone who knew Lorca. (Incidentally, I recently discovered that José Luis had drawn on his memories of Russell when creating one of the main characters of his novel Señorear la tierra (1991).)

Woodstock Road en julio is an account of the 48 hours José Luis spent in Oxford in 1994: a flying visit made more than a decade after the author moved back to Spain. More precisely, it recounts his impressions on revisiting and recalling people, places and events from a time when “although I didn’t realise it, I was happy” (my paraphrase).

Mis-remembering is the theme

Deliberately or almost certainly not, the text is riddled with mis-spelt English (e.g. Tatcher, Rutheford, scons, Bogart for Bogarde, Merlyn Strep… ) Despite living in the same house in Woodstock Road for three years José Luis can’t be sure which one was his. “How is that possible?” he asks: the house where he was happy, spending time with his young son, Daniel, on Saturday mornings; the house he only left because his Oxford tenure had come to an end.

He redefines nostalgia

It is, he says, not the pain of absence but the pain of returning; of knowing that the people and things you left behind can exist without you, and you without them. “The pain of change, the pain of time.” A return long delayed in his case because, with the passing of time, the pain gets stronger.

I regret losing touch with José Luis. Of the four university lectores I knew at Oxford – Vicente Molina Foix (1976-79), Félix de Azúa (1979-81), JLGF (1981-83) and Javier Marías (1983-85), all of them important writers – he was perhaps the most open.

***

Anyway… in the opening pages of his sentimental journey, while whizzing along the M40 on the X90 bus, José Luis recalls making the same trip in his red Panda from Holland Park to Oxford in January 1982 (as I write, almost exactly 43 years ago). Snowflakes were falling as he left his friends’ house. If his car had been equipped with a radio, José Luis would have known to stay off the roads. The journey took five hours rather than the usual two. The temperature dropped to -17C as he approached Headington in a nightmarish blizzard, the Panda crawling along in second gear past abandoned vehicles, hardly able to see through the windscreen.

I remember that winter well

Jude and I had spent Christmas 1981 with her family in Wolterton Hall, a stately home in Norfolk her family had rented for a week. As we exchanged presents and sang carols by a blazing log fire, the snow outside really was deep and crisp and even. December was unusually cold but worse was to come.

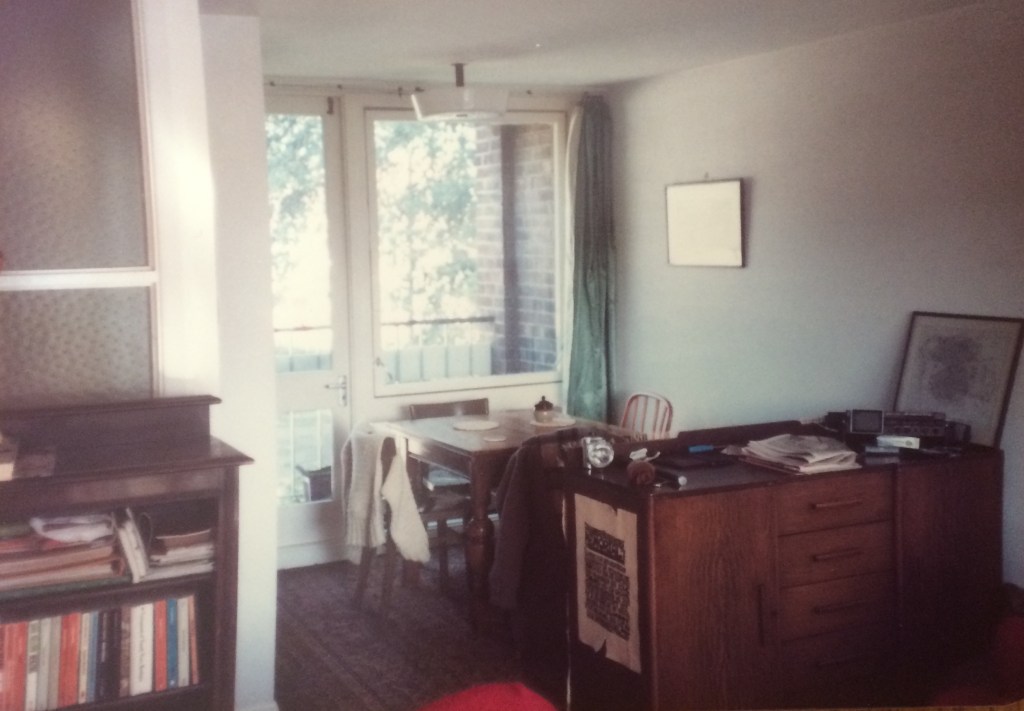

Our end-of-terrace flat in Littlemore, East Oxford, was rented from Margaret Krebs, widow of Nobel-prizewinner Sir Hans Krebs. Built in the 1960s, it had large, badly-insulated windows out of which leaked our expensively fan-heated air.

***

As José Luis was making his laborious way through Oxford to St Giles’, Jim Chambers, a fellow Spanish seminar member, arrived at our flat for dinner. It snowed that night and kept on snowing, and the city ground to a halt. The next day the temperature dropped to -23C. When you ventured outside for provisions your lungs hurt with each breath; it was colder in the Midlands than at the North Pole. Ice formed on the inside of our windows and the ballcock of the water tank froze and jammed. I had to climb into the loft and unfreeze it every morning before we could wash. Jim stayed for three days because there were no buses and it wasn’t possible to walk home through a foot of snow. He was good company. Again, we lost touch.

Random rememberings…

In spring I invited José Luis round. At first he refused a glass of wine because he had a stomach ulcer, but soon relented/relapsed. I recall that he pronounced kamikaze as “kamithake”, and I wondered if he were dyslexic, which might explain the typos in Woodstock Road. But he was an editor as well as an author so that makes no sense!

***

I had a grant from Queen’s to travel to Corunna to examine some manuscripts. John Rutherford offered me a lift in his Peugeot 504 and we caught the ferry to Santander, arriving on 3 April just as the Falklands War (“Folklands” in José Luis’s book) was kicking off. Almost the first people I spoke to were an Argentinian couple on holiday. We were all sure it would be sorted out by mysterious diplomatic means.

But we were wrong

Back home in Oxford, I would watch the News at 10 in the pub as things went from bad to worse. On 2 May General Belgrano was sunk by a torpedo. Two days later HMS Sheffield was hit by an Exocet missile. Men were dying in their hundreds and we were all watching in disbelief. Yet another member of our graduate seminar, Daniel Waissbein, was from Argentina. It was a horrible time to be a student of Spanish, especially if you loved Jorge Luis Borges and the tangos of Carlos Gardel.

José Luis says in his book, and I remember us discussing it at some college do or other, that he was shocked at how easily the British public accepted the deaths of so many serviceman, which would certainly not have been the case in Spain. I replied that I thought it was because we had a professional army rather than conscripts; somehow that made it easier to accept. This, too, José Luis refers to in Woodstock Road.

A turning point for me

As 1982 drew to a close I admitted to myself that I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life as a university lecturer. Many academics I knew seemed to hate each other. I was bored with my slowly-developing thesis and my heart was no longer in it. I blundered along for a couple more years before I left Oxford for London, got a job, finished my thesis at last and began to grow up. The possibility of change, the possibility of stability and real happiness edged a little closer.

***

In August 1985 José Luis invited me to spend a fortnight with him in Cadaqués. After an unfortunate start, when he failed to meet me at the Maritim Bar and I had to spend the night stretched out in an olive grove, I had a splendid time. I drove the red Panda to the shops, we swam before lunch, I helped out with the olive and almond trees, we played cassettes on his stereo. I was invited to a tremendous party given by the (Communist) ex-mayor; there was skinny-dipping, literally buckets of premixed gin-and-tonic, and barbecued lobsters all round. It was the nearest I’ve ever got to taking part in an orgy and I am resigned to never seeing its like again.

We talked about compiling a new anthology of Spanish poetry, for which I was to do the translations. I pitched the idea to Penguin (who rejected it) and Manchester University Press (who said they were considering it).

But in January 1986 I started a job at the British Library. José Luis found a new job too, and it was pretty clear that the “project” he refers to on the flyleaf of his poetry anthology El largo adiós was never going to happen. However it is nice that he had thought I was up to the job.

José Luis died in 2008 at 63

Alas, it’s too late to thank him for putting down his Oxford memories, many of which coincide with my own.

***

I, for one, no longer find the remembering and forgetting and re-remembering of events that happened, or nearly happened but didn’t, painful. The question is: “Am I the same person I was four decades ago?”