It may have passed you by that last week was the 50th Anniversary of Portugal’s Carnation Revolution. On 25 April 1974, suddenly and almost bloodlessly, the Estado Novo, a fascist dictatorship that had endured for 48 years, came to an end.

I was a first-year student at The Queen’s College Oxford at that time: the holder of a certificate declaring that I had passed my First Public examination, having studied Portuguese for two terms (i.e. 16 weeks).

Why was I studying Portuguese?

As I explained in an earlier post, I needed a second language to go with Spanish and starting Portuguese (rather than building on my O-Level French) seemed like a good idea at the time.

Clearly not many fellow freshers shared my optimism, because I was the only undergraduate that year to take up Portuguese across the entire university; examination papers were printed for my sole use. Contrary to what I had hoped, Portuguese was not easy to learn, even though I had studied Latin, French and Spanish at school; fortunately I also had youth on my side.

But I stuck at it

I had never been to Portugal before, but was due to go in July 1984. Did my grant to study for six weeks at Coimbra University’s summer school still hold? Was it safe to go? I crossed the water from Birkenhead to the Portuguese Consulate in Liverpool. A helpful young woman (only the second Portuguese person I had ever met) rang the Ministry of Culture in Lisbon, who assured me that everything was in order. I walked on to the NUS office and booked a discounted flight to Lisbon. At the age of 19 I would be travelling into the unknown.

It was very exciting

And so, less than three months after the dawn of its brave new democratic era, I set foot in Portugal for the first time. It was roasting hot, reassuringly cheap, and the people were polite and helpful. It reminded me of Greece: old-fashioned, not to say backward, in a picturesque way. I was a phenomenon: a foreigner who spoke Portuguese, if hardly fluently. Just as well I did, because no-one spoke English; not that I was expecting them to.

The only obvious evidence of a revolution was the political graffiti, though I didn’t grasp much of it… all those acronyms!

When I arrived in Coimbra, a student explained that it was the crippling economic and social cost of maintaining the African colonies that had led to the demise of the old regime. At one point 25% of the male population was conscripted into the army; and it was bloody dangerous out there. There was a propaganda map which, in translation, reads “Portugal is Not a Small Country”; at one time it hung in every school.

By 1960 the age of European empires was clearly at an end but Portugal, the poorest country in Western Europe, maintained that Mozambique, Angola, Guinea, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Goa, Damão, Diu, Macau and Timor were not colonies in random parts of the globe but “overseas provinces”. In reality they had become a millstone around Portugal’s neck. Finally the Armed Forces under General António de Spínola (later, President of the Republic) decided that a change of regime was essential. Muito obrigado Dr Marcelo Caetano, e boa viagem a Madeira!

Even as a newly arrived foreigner I understood that it was a time of celebration and hope for students and liberals, and of some trepidation for the professional middle classes. Of course there were to be serious consequences: civil wars in Angola and Mozambique killed thousands, with a consequent refugee exodus. It was not an orderly withdrawal.

This was my first proper taste of learning to get by in someone else’s language, and adapting to someone else’s culture, if only for six weeks.

It changed my life

***

Portugal was a country that few people visited in the early 70s, although it did have a tourist industry, principally in the Algarve. After leaving university I got my first serious job, as assistant to the manager of The Travel Club of Upminster, an innovative and well-respected family-owned business. At one time 50% of all British tourists to the Algarve went with them. Quite unexpectedly, studying Portuguese had turned out to be of some practical use. Working for a tour operator brought obvious perks but in October 1978 I decided to return to Oxford and study for another “few years”.

Since then I have been back to Portugal many times. This year’s trip to Goa, as well as earlier visits to Malindi and Mombasa, were informed by what I had learned (though surprisingly little!) about Portugal’s 500 years as a colonial power.

And then to Spain

My third student year (1975-6) was spent in León in Spain. Again, I have already written about it on this blog so I won’t repeat myself. I’ll just say that it was a happy time when – although in retrospect I did lark about far too much – I started to grow up.

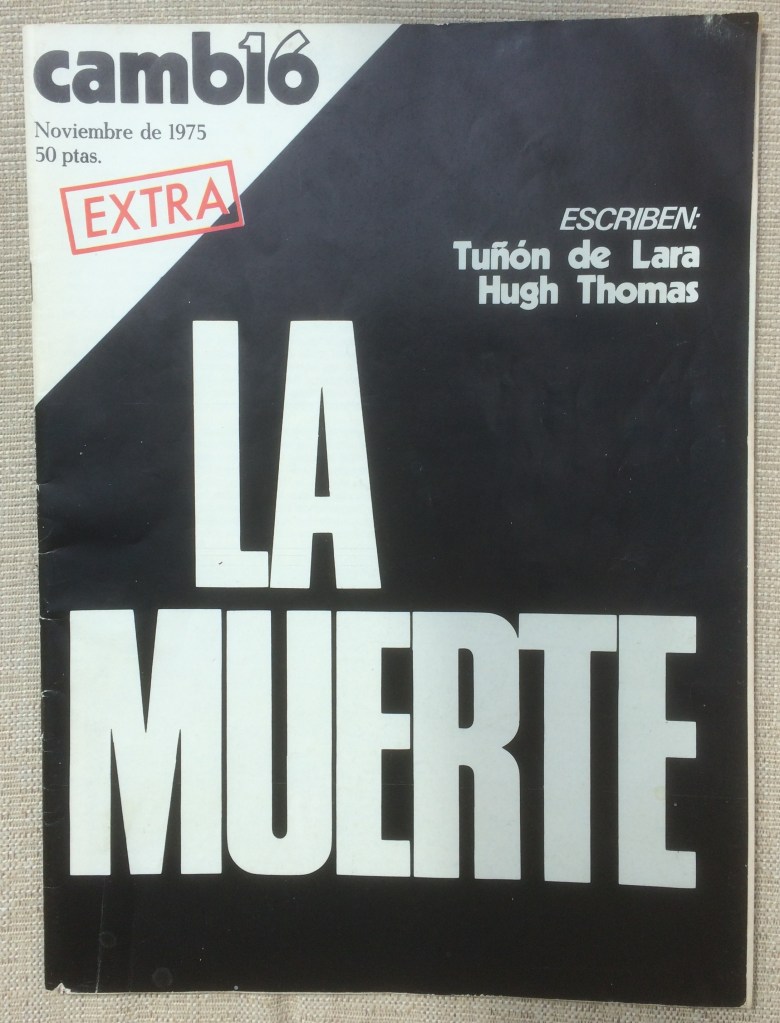

No sooner had I arrived than another long-lasting fascist regime fell apart, with the lingering death of Francisco Franco.

What a privilege it was to witness key events like this from close up. Not only to have been there at the time, but to have heard and understood the radio and TV reports, to have read the newspaper reports in their original language, to have had long discussions with local people about what might happen next.

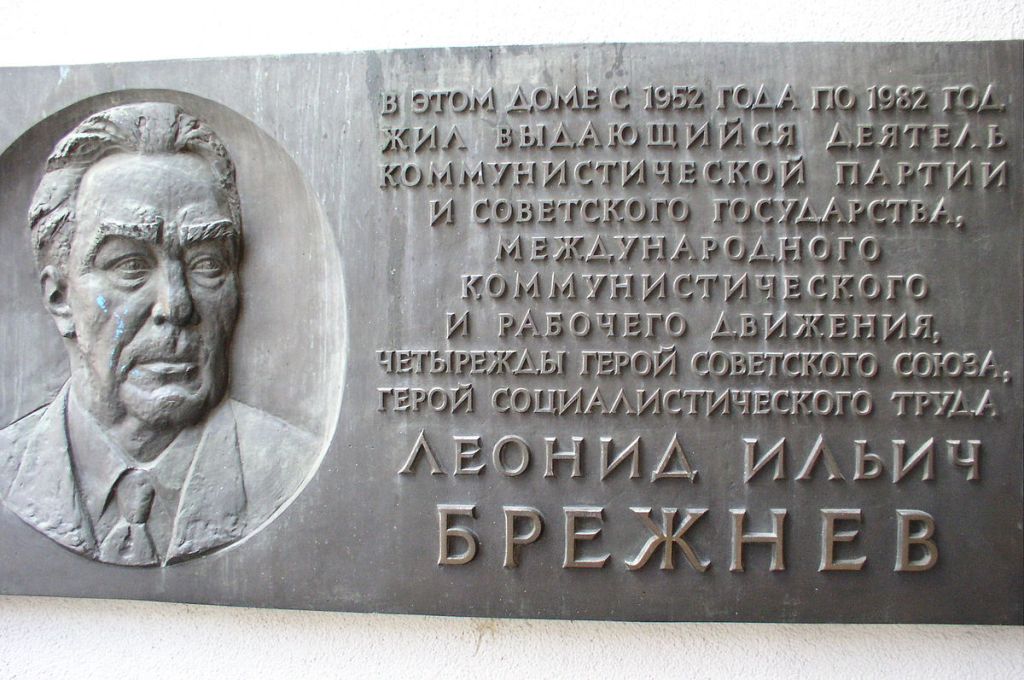

I was in Moscow in 1982 when Brezhnev died (although officially a tourist, I was travelling with a post-grad student of Russian culture so I was well informed). I have strong memories of that week: lugubrious Beethoven and Chopin on the radio, the lock-down and, bizarrely, the church service for the soul of our (atheist) brother Comrade Leonid Ilyich.

Think like a linguist

I was back at Queen’s once again last month for a Mod Lang graduates reunion. It is a beautiful college (I am not denying that I was privileged to have the opportunity to spend eight years there) and I am always pleased to be invited back.

Modern Languages has long been one of the College’s strongest suits, but what value is given to foreign languages today? Sadly, fewer and fewer young people are studying languages at school (although Spanish is doing comparatively well). It is not seen as important. After all, everyone speaks English nowadays. That this can be offered as an excuse is bad enough (even if it were true), but I want to shout out, “that’s not the point!”.

You make friends for life, meet people who have a quite different history and culture; start to question what you thought you knew, to understand better what’s going on around you rather than being a passive victim. In time you will learn to write better, clearer English. What does this word mean? What other words could you use and what does your choice imply? Is less sometimes more?

***

The fact that my Spanish tutor was a dedicated translator clearly influenced my way of thinking.

But it’s not my job to put the argument to schools. Queen’s has been very active in setting up initiatives under Dr Charlotte Ryland to promote the cause of language study, among which is a project that brings recent graduates into schools to encourage children (and teachers) to explore the challenges and fun of translation, even if they hadn’t ever thought of it as relevant, let alone an option at university.

That’s why I have decided to start supporting the Queen’s Translation Exchange. I look forward to seeing what develops.

One thought on “Think like a linguist”