October 1979: I was still, or again, (depending on which way you looked at it, as I’d returned to do post-grad work) studying at The Queen’s College Oxford. The college offered me the exalted if ridiculous-sounding position of Vir Probatus (Junior Dean) if I abandoned the freezing slum that was 41 Bullingdon Road and moved into James Stirling’s infamous Florey Building on St Clement’s. As I’d have the largest room in the building, rent-free, with a free telephone line to boot, I accepted.

An unexpected bonus was that the underfloor heating and huge windows offered an excellent environment for cultivating aromatic, jagged-leafed plants. I’d stayed there as an undergraduate so the building itself did not come as a shock. Much has been said about it…

One of the older students at the Florey was Denis, who was writing his DPhil on Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina draft manuscripts. He was witty, kind and urbane, and like an uncle to me. There wasn’t much he did not know – about human nature, in particular. He had two teenage children by his first wife and a little boy by his second wife, who taught History of Art at the University of Essex. (Later they created the nom-de-plume Natalya Lowndes and wrote a series of novels together.)

Denis and I spent many a lunchtime in the poky-cosy Half Moon in St Clement’s, at that time managed, if that is the right word, by the Leaves brothers.

Regular patrons included Steve Winston, owner of Winston’s, the night club next door, and Pat, manager of the Private (i.e. dirty mags and videos) Shop in Cowley Road. The Half Moon offered real ale, had no fruit machine or jukebox, and hosted live music on Sunday afternoons. Just my sort of place.

***

October 1982: I’d moved out to a flat in Littlemore at the eastern extremity of the city, but Denis, still my regular drinking partner, held on at the Florey. He told me that he needed to do a week’s research in Moscow’s libraries, and the cheapest and easiest way of doing that was to book an Intourist package.

Never having been to Russia, I was happy to share a room

***

A couple of years earlier the BBC had launched a series called Russian Language and People. It featured a beautiful brunette presenter called Tanya Feifer and a beautiful blonde interviewer called Tatyana Vedeneyeva. (By one of life’s coincidences, Tanya’s co-presenter, Edward Ochagavia, is a neighbour of mine in Herne Hill.) Into each episode was inserted a snippet of a corny love story called До свидания, лето (= Goodbye Summer) with Victor, the ordinary-looking taxi driver, and Olga, a fantastically beautiful student.

It was 8 November, and snowing in a picturesque way, when we cleared passport control. My visa was numbered 007, but even I didn’t think it was a good idea to make a joke of it. Denis advised me to stare grimly ahead while my features were scrutinised. At last we arrived at our shabby hotel, the Intourist, a few minutes’ walk from Red Square.

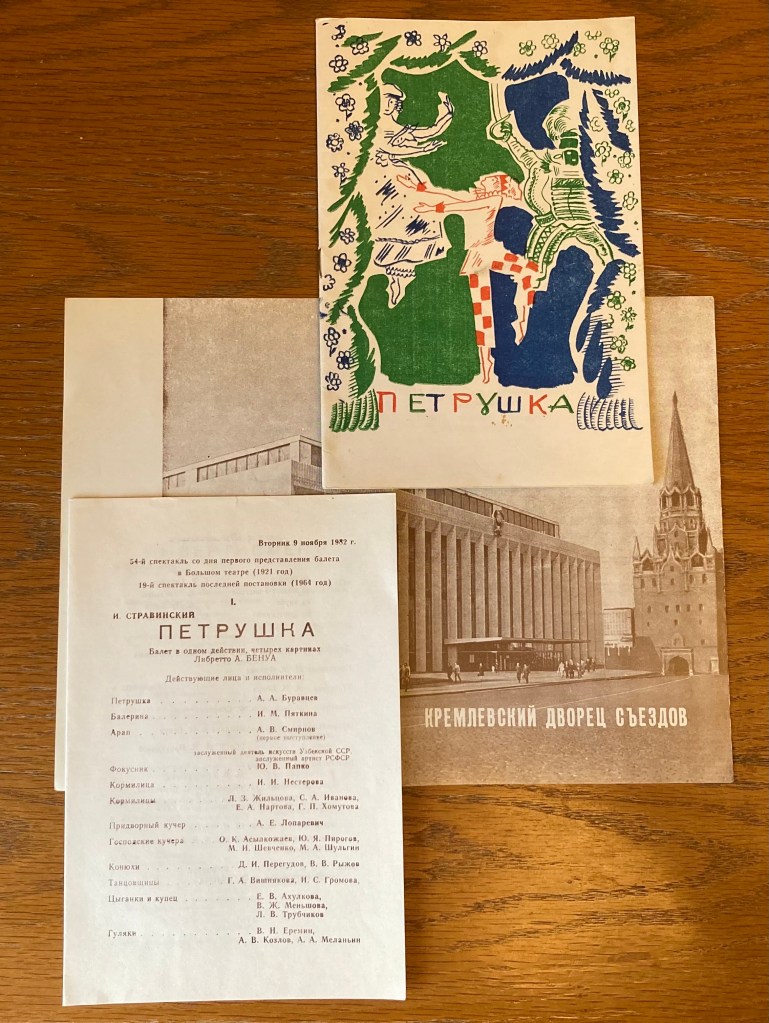

The following evening I went on my own to see the Bolshoi Ballet perform Petrushka: something most Muscovites could never afford to do. It made a deep impression on me and I loved it.

The plan was to meet Denis afterwards at his friends’ flat. I hailed a taxi at the Palace of Congresses and indicated the address Denis had written out neatly in Russian. “Victor” grunted and I attempted to make small talk in English… then in French, German (of which I know about 50 words), Italian and Spanish… to no avail. There didn’t seem much point in trying Portuguese, Latin or Ancient Greek. I persevered with the very few words of Russian I knew. He didn’t want my roubles and I had no dollars. He said “pen”, and I paid with a partly-used BiC ballpoint.

Хорошо, спасибо, До свидания!

I found myself in an ill-lit street of run-down tenements, rather like the half-remembered Glasgow of my childhood. It was quite scary. I climbed the staircase to the second floor in trepidation; what would happen when someone opened the door? What if Denis hadn’t arrived or I’d come to the wrong place?

But Denis came to the door

In the little flat were a middle-aged couple and a girl in her early 20s. She was slim with long dark hair, like Tanya and, I couldn’t help but notice, very pretty. Everyone was smoking black Georgian cigarettes. I took a chair, and a large Столи́чная vodka was poured for me. And so began an interminable evening of music, “conversation” and toasting. Their favourite record was “The Sideboard Song” by Chas and Dave, which Denis had brought with him on a previous trip. Perhaps the A-side, “Rabbit”, was played out. I contributed “Things We Said Today” by The Beatles, on a very bad, untunable guitar. More beer and vodka and pickled cucumbers. A dinner almost guaranteed to stop you from sleeping. More songs.

Uncle Yuri would tell a joke and everyone would laugh; so did I, out of politeness. Denis would explain it to me in English and I’d laugh again. Luckily for me the pretty girl, Katya, was fluent in Spanish. Katya would then ask me in Spanish what he’d said. I would explain it to her and she’d translate for her mother. She’d tell Denis, in Russian, who would then tell me, in English, that he’d said something quite different. A single joke could keep us going for 20 minutes. When they did get through, the Russian jokes were good: they were steeped in a world-weary irony and bitter sarcasm that we Britons found familiar.

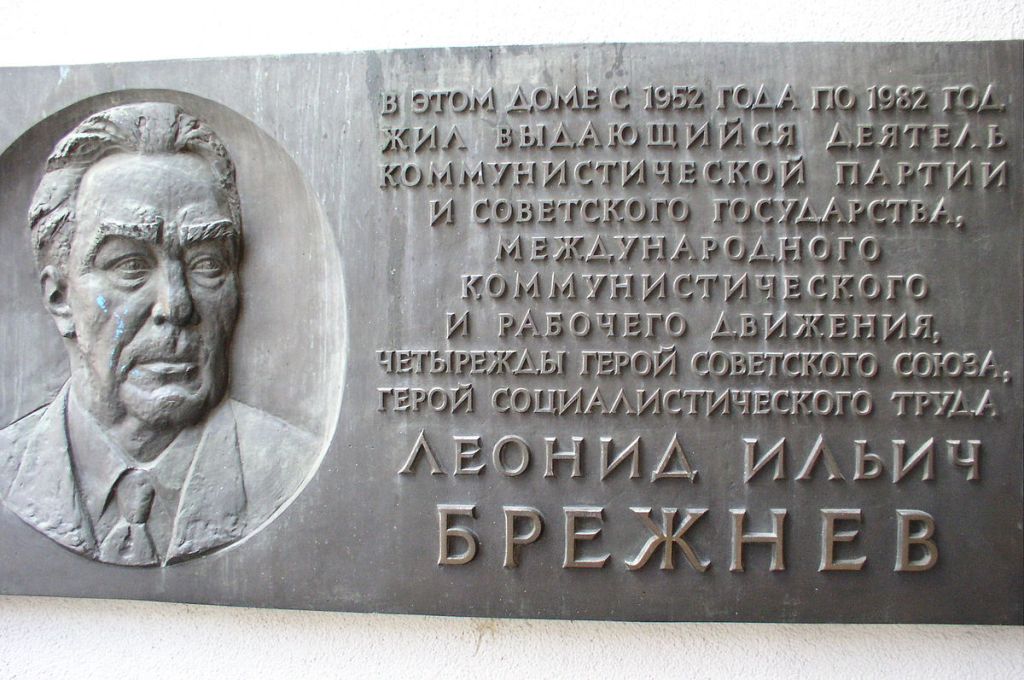

What we didn’t know, was that as we’d touched down at Sheremetyovo airport, Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev was dying. He died on 10 November, the day after I’d gone to the ballet. Soon the city-centre was put in lockdown. It was snowing hard; the Kremlin was closed, the national museums were shut, and taxis could not get across town. Moscow was in official mourning and all you heard on the radio and black-and-white TV was Chopin and Beethoven. We were moved out of our characterful old brown hotel with its tea-ladies, and into a soulless modern one by the VDNH exhibition centre. Every available room in central Moscow would be needed for the dignitaries arriving to pay their respects.

We were on a full board deal, but most evenings Denis and I took the metro to the flat, bringing food we’d bought for hard currency at the Beriozka. The two grateful women cooked for us. In the afternoons Katya showed me the sights, and we trudged through grey, dimly-lit streets in the snow, rain and gloom for hours on end. She really was attractive, if a bit skinny — probably because she wasn’t getting enough to eat. I kissed her once or twice, in Spanish of course.

Obviously Katya and I would not meet again

Except that… a couple of years later Katya managed to get a job in Riga as a translator, then met and married a solid Englishman called Mr Smith, and made her escape to Wimbledon. News of her arrival filtered through to me.

One evening she joined us for dinner round the kitchen table in Brixton. I invited her again and she forgot to come. I invited her a third time but, once again, no show. I didn’t give her another chance – I can be cruel that way. The new Mrs E. Smith had lost Katya’s aura of mystery… and I lost her address.

Great post Colin. That last sentence is particularly excellent. I love your writing.

The blog is cheering me up as I have been sitting in a stationary car in a snow induced jam on the frozen wastes of the A38 outside Exeter for 2 hours! Who forgot the blankets and spade?

LikeLike

Thank you Sheena. Chin up! Though that’s easy for me to say x

LikeLike